30 Mar Interview with Adelmo Dunghe, SJ

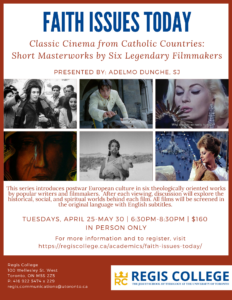

Regis College will relaunch Faith Issues Today as an evening companion program to the popular Windows on Theology Series this spring. This upcoming edition of Faith Issues Today will run in person on Tuesdays from April 25 to May 30, from 6:30-8:30 pm. More information and a registration form can be found here.

Regis College will relaunch Faith Issues Today as an evening companion program to the popular Windows on Theology Series this spring. This upcoming edition of Faith Issues Today will run in person on Tuesdays from April 25 to May 30, from 6:30-8:30 pm. More information and a registration form can be found here.

In this offering of Faith Issues Today, Regis alumnus Adelmo Dunghe, SJ, will be presenting “Classic Cinema from Catholic Countries: Short Masterworks from Six Legendary Filmmakers.” Adelmo completed his Ph.D. in Theology and Cinema and taught at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia for many years before returning to Toronto to serve at Our Lady of Lourdes Parish. Below, Adelmo gives us an insight into his love for theology and cinema, how cinema can be an encounter with God, how he chose the films for his offering of Faith Issues Today, and what he hopes attendees will gain from the class. Thank you, Adelmo, for your insights, and Regis is delighted to have you present the first relaunch of Faith Issues Today.

What motivated you to study theology and cinema?

From a very young age I was introduced to international cinema. Fortunate to have grown up in Buffalo where masterpieces of world cinema could be seen regularly on Buffalo and Toronto television, I was exposed as a very young teenager to works by such great filmmakers as Federico Fellini and Ingmar Bergman. In Buffalo especially there was a local television station that was programming most of Bergman’s films from the 1950s and a lot of early Fellini, too, and on Saturday evenings my sister and I would usually watch one of the Toronto stations (the CBC, I think) that introduced us to things like Fellini’s Otto e mezzo (8½), Kubrick’s Lolita, and De Sica’s Condemned of Altona.

Since Buffalo was going through something of an artistic renaissance in the late 1960s, it was easy to find the latest foreign films being screened at the Albright-Knox art gallery, at a little independent “art cinema” not far from our home, and on the campus of the University at Buffalo. As much as I could, I involved my parents in taking me to these screenings, since my age made it difficult to get to (or be admitted into) some of these venues. So by the time I was 16 or 17 my parents started to enroll me in “credit-free” international cinema courses at U.B. There I encountered familiar and unfamiliar works by my “old friends” Bergman and Fellini, and was introduced to new and old films by other masters such as Rossellini, Godard, Truffaut, Pasolini and Bunuel.

It was early in my teen years that I also started to formulate the idea of a religious vocation, and I think my fascination with all things theological were what drew me into the visionary worlds of so many of these masters of cinema – Bergman, the son of a Lutheran pastor; Fellini, the eternal Catholic schoolboy; Pasolini, who dedicated a film to Pope John XXIII); and Bunuel, a product of Jesuit education. Unlike most of the American films I was familiar with, many of these foreign films were very blatant in their narratives’ explorations of theological themes, and, along with priesthood, I also was attracted to the idea of becoming a filmmaker myself.

But as a teenager I couldn’t grasp what would be necessary to accomplish any of these long-term goals, so I wound up at the University at Buffalo, majoring in English (the department where cinema studies were housed at the time) and turning in term papers (or short 8mm films) on topics like “The Book of Job” and The Castle of Perseverance. My own worldview, like those of the filmmakers I most admired, could not be separated from religion.

How can cinema be an encounter with God?

For me, any film that dared to put God front-and-centre in its narrative was worth studying. To paraphrase both Ricoeur and Pasolini (the two main authors of my doctoral dissertation at Regis), any work of literature (including cinema) is a “world” which the reader is invited to enter so that the world of the text may interact with the world of the reader’s own experience to produce, to a greater or lesser degree, a transformation in that reader’s experience. It’s my opinion that if God has been allowed into the world of the text by its author, the filmmaker’s concept of God will resonate with the world of the reader. Again, this is why I was always attracted to those foreign filmmakers who made some sort of connection with God and/or Church integral to their narratives. I’m not too interested in taking a completely secular work, typical of modern Hollywood, and using it to elaborate on my own religious ideas that likely were not there in the film text to begin with. It’s hard to explain this in a simple way.

How did you pick the films you will be using in this course?

The six films I’m using in the course are rarely seen short works by world-class filmmakers from Catholic countries, films that do place theological ideas front-and-centre in their narratives. All of them are by filmmakers whose longer works I regularly use in my Theology-and-Cinema courses, and it’s these shorter films that I often have students analyze on their final examinations.

What do you hope attendees would receive from participating in your course?

As I mentioned in my brief course description, I see the purpose of this course as twofold. First, to show students that, as these filmmakers from Catholic cultures demonstrate, cinema can serve as a medium of theological discourse. (This is certainly what seems to have impressed my graduate students when I taught a Theology-and-Cinema course a number of years ago at Regis College.) Second, I feel that it’s always appropriate to consider how the art of cinema has evolved since its inception some 128 years ago. This will be especially interesting since many of the filmmakers we will look at in this course represent movements from the mid-20th-Century that have impacted the way films are made today.