21 Sep Art in the House (RFQ 4.1)

Posted at 05:00h

in Regis Friends Quarterly

In a now distant spiritual mindset the Baltimore Catechism encouraged students to turn their gaze to the crucifix.

In a now distant spiritual mindset the Baltimore Catechism encouraged students to turn their gaze to the crucifix. “If we knelt down before a plain white wall we could not pray with the devotion we would have kneeling before a crucifix,” Msgr. Januarius de Concilio wrote shortly after the 1884 Third Plenary Council of Baltimore, which mandated the famous American catechism. “We see the representation of the nails in the hands and feet, the blood on the side, the thorns on the head; and all these must make us think of Our Lord’s terrible sufferings.”

Though it came out of a notably synodal process, the Baltimore Catechism is not much loved today. Its Jesuit roots in the 1614 Catechism of St. Robert Bellarmine are hardly ever mentioned. But wander from classroom to classroom, from the chapel to the administrative offices of Regis College, and there are many opportunities to follow the Baltimore Catechism’s advice on devotion to the cross of Jesus – many opportunities to see in a variety of crosses a much wider theology than the narrow focus of the Baltimore Catechism.

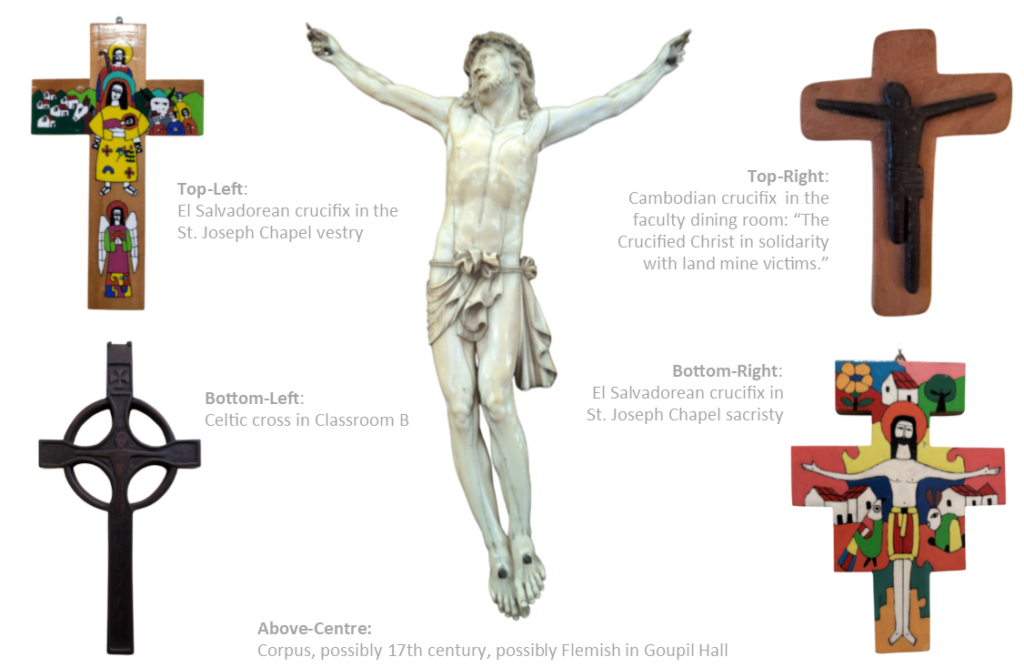

A catalogue of 18 of these crosses reflects the global reality of the church and the multicultural ambition of the Jesuits’ graduate school of theology. There are crosses from Cambodia, Ukraine, Ireland, Holland, Italy and Central America.

In Goupil Hall there is a magnificent corpus, floating free of its original cross, that shows exactly what the Baltimore Catechism had in mind – a 17th century, likely Flemish, image of suffering and sacrifice intended to draw us into the humanity of Christ in his passion.

But the ringed Celtic Cross in Classroom B has other concerns. Images of Christ on the cross like this one have been around in Ireland and the British Isles since the early middle ages. Some trace the design back to St. Patrick in the sixth century. The ring surrounding Jesus symbolizes a kind of unity that encompasses all of creation. It expresses a Celtic faith in infinite compassion, infinite love.

In the third floor faculty dining room there is a crucifix for our unpeaceful age. Designed by the Jesuit Education for the Disabled at Banteay Prieb, Cambodia, it depicts “The Crucified Christ in solidarity with the land-mine victims.” Even as nations now begin to walk away from the 1997 Ottawa Treaty that banned land mines, this image of Christ with his leg blown off below the knee is a reminder of the six million land mines scattered haphazardly through Cambodia in the ‘90s, and the resulting carnage of innocent civilians that inspired this treaty.

In the chapel, look for two Salvadorean crosses – one above the vestry and the other in the sacristy. These are the grandchildren of Salvadorean artist Fernando Llort Choussy and the folk art school he established in the small town of La Palma, Chalatenango in the 1970s. The history of this kind of imagery on crosses throughout Latin America goes back centuries, but Llort and his Foundation for Self-Sufficiency in Central America (now renamed EcoViva) established a particular style recognized around the world.

The background images on these Salvadorean crosses of green mountains, farmers, cattle and flowers surrounding Christ are intended to include and display campesino identity within the widening ambit of Christ’s passion and resurrection. That identity was precious to Llort and his friends even as they endured a long, ugly civil war through the 1980s.

Though the Salvadorean images appear naive and even childlike, Llort studied philosophy at the University of Toulouse, earned a theology degree from the Université catholique de Louvain in Belgium and then took classes in art and architecture at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. His work has been compared to the art of Joan Miro and Pablo Picasso.

Among all the crosses of Regis there are many opportunities to do what Llort was seeking for his campesino artists in La Palma – to find a gateway into our identity on the cross.